The next dispatch from Saumya, sorry this is late to post! – Kate

Mataji,

Dal Kachoris,

and gassy nostalgia

The time it takes to retrieve a memory with little form or structure, is the time it takes to make my Mataji’s Dal Kachori from scratch. Both provide nostalgia in varying measurements of tangibility, in waves, in the kitchen, especially on the 10th of February, for the last 10 years.

All in the span of a Day.

In an early morning, FaceTime chat with my parents, my father in a fleeting manner, reminds me of Mataji’s birthday. Not that I have forgotten, for some birthdays are etched into your being and no matter how much time has passed, you continue to recall them. What I have trouble remembering is, everything else. There are gaps in my memory when it comes to familial childhood, one with temporary landscapes and nuclear living. There is an even bigger gap in the story for me when it comes to my parents' childhood and my grandparents' childhood. Sometimes, the preoccupation from the nth ‘todays’ layers these disembodied, ethereal memories with dust. In times like these, when rain stains start drying up, and our memories continue to evaporate like raindrops, I suggest using a vessel to collect, contain, or just trigger. Like a Dal Kachori.

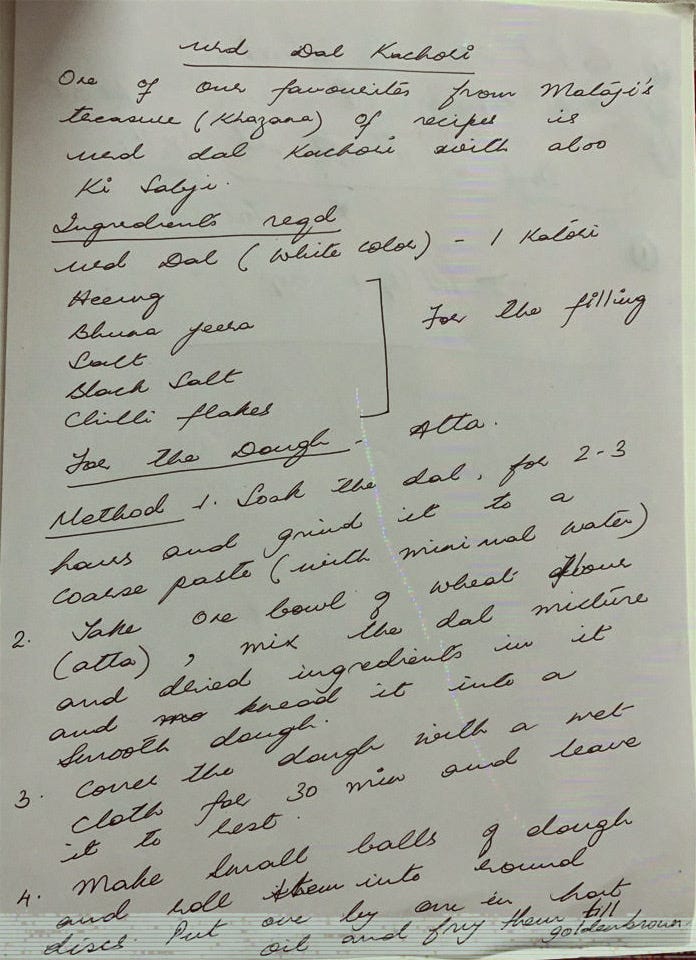

I am writing this from the kitchen counter. Not the island, but the little alcove next to the stove, with my hip propped against the cabinet, hunching over my keyboard, watching the lentils fully submerge in water, waiting on the rogue ones to clear the surface. Of all things that drove men in the Indian patriarchal society out of the kitchen, the most common adversity, I have come to learn, is patience for the dal to soak. Next to me, is a printed image of a handwritten note by my mother, for a message on WhatsApp won’t encapsulate her cheeky side notes. It’s a recipe- titled

‘Urd Dal Kachori-

One of our favourites from Mataji’s treasure (Khazana) of recipes is the Urd Dal Kachori,

with Aloo ki Sabzi’

The time that it takes for the rebellious little balls to soak is the time that it takes for my brain to internal scout (it has tried, many a time to localise and store, all efforts in vain), submit applications to release chemical matter from neuron to neuron, juggling within the synapse-familiarising the memory with the rest of my body. I am beginning to remember. The scent of her talcum powder; her milky-white, flawless yet loose chubby skin, especially under her arms, something I remember kissing a lot but also playing with, in a swinging motion. Her husky and hoarse, yet high-pitched voice. Her very (sans) toothy smile. I know memories don’t exist in a concrete form, but somehow the feeling here is tangible. I call my father again, and what happens next can only be described in Graham Greene’s words- “A story has no beginning or end: arbitrarily one chooses that moment of experience from which to look back or from which to look ahead.”

He is driving and talking, a very common practice on Indian roads, as he regales me with a colourful account of her visit in her 93rd year to Tibri. A small Cantonment in the innards of Punjab, where we lived for a year in my early teens. It has been 3 hours, and the dal looks like it has absorbed the water it had been commissioned for. I ask him to pause, as I put it in the grinder and make a paste. We resume talking about her penchant for waking up at 4 in the morning; a practice she had sustained for most of her life, and doing her Mala. A Mala is a loop, traditionally composed of 108 beads. It is said to hold the energy generated during our prayer practice.

Towards her later years, her mala was often interrupted by the sounds of her snoring, sitting upright, which would also abruptly bring her back to her practice. My father has a dreamy, awe-struck smile stuck to his face as he points out that she had this regality she exuded, even if it was post an early morning shower, and she was dressed in a comfortable nightie. White, the colour of her nightie with some dainty flowers, the colour of her hair coiffed in a high bun, and her statement jewellery in place. We can’t remember a time she wore gaudy colours. She preferred to dress in pastels, but my memory has hitched its wagon to her white.

Currently, I have zoned out a little, and I am staring at the recipe in front of me, like a camera with its lens open; compliant, documenting, not thinking. My father randomly cracks up thinking about the time she asked him how much sugar he wanted in his tea, and he responded with an ‘itni si, mataji’, holding his thumb to the first quadrant of his index finger, and without missing a beat, she told him “davai bhi itni si hoti hai”. It loosely translates to– a medicine that can cure your entire body ache comes in that size too. My father says “She never hesitated to speak her mind and always kept us on our toes with her quick comebacks and witty remarks. She was a true original and a master of one-liners.” I am leaning against the counter as I ask my dad about his favourite dal kachori story, and he throws out a quick joke about our (mataji’s and my) height. Coincidentally, or maybe the memories from this particular trip act as a catalyst, he tells me about her making the kachoris in Tibri. At 93, when asked by the family to make her famous Kachori’s, she insisted on doing it all herself.

When her husband passed, many many years ago, she began to intermittently live and shuffle between her children’s homes. What I find interesting is, everyone in the family describes her as a very non-intrusive guest or family member in the house. If one knows anything about an older Indian woman and the kitchen, it's their codependent relationship, and their need for asserting power, thereby showcasing dominance, which leads me to believe, for the last 30-odd years, she wasn’t a regular in the kitchen. Yet, I suddenly have a vivid recollection of her propped against the edge of the counter, much like me at this moment, her hands a blur as they chop, mix, and stir the ingredients in front of her. I can tell she's been doing this for years, decades even. Her movements are practised, almost choreographed. My father goes on in an amused tone, reliving how she would call him every time a single kachori was ready for consumption. My dad, trying to maintain his ideal weight, would complain and moan, stating she previously snubbed him for the sugar in his tea. She conveniently ignored his protests, retracting her quip and pacified him into eating them all. The ever-doting food hypocrite.

I suddenly find myself in an angular position on the couch, and jolt back into my immediate surroundings, acutely aware of the kachori’s that still have to be prepared. I tell my dad I want a picture of her for this passage I am writing, and that I’ll call him later, as I proceed to prepare the mixture for the filling- Asafoetida, roasted cumin, salt, black pepper, chilli flakes. Thereafter, I start on the dough, adding some water to the flour and start kneading. My brain is carefully blank and set on the task of making this kachori a success. For some reason, kneading the dough really takes it out of me. So, in the 10th hour of making this delicacy, as the picture rolls in, I take yet another break….

In a way, I kind of have these "inception" memories. Copies of a copy of someone’s memory. Looking at her younger self, I try to consolidate and homogenise collections of stories from her children, grandchildren and my nascent recollections of being an inner presence, baffled by the generational gap. Hailing from an affluent family, she was married at the tender age of 16 in a suffocatingly patriarchal era, to a respectable officer holding a rank in the British Army. He passed away fairly early in her lifetime. She gave birth to 5 boys and a girl, some of whom she outlived. Imagine the pain of losing and cremating your children, only to stand tall and provide solace to her loved ones, and admittedly take comfort in the fact that it was beneficial for them to leave, to be rid of their suffering. She, who was born under the colonial rule, and having witnessed not just the era of Independence, but surviving the mayhem that it brought with it. Family members say- they travelled across the newly formed borders with little possessions of their past and the clothes on their backs. I think she bore a heavier burden. She travelled with a responsibility towards her children; of culture, love and patrimony left in their past, and of reconstructing this intangible heritage in a new world, one with undefined rules, and unending chaos. She, of her dainty whites, her coiffed hair, her young marriage, and her affluent upbringing- unknowingly assumed the role of a Matriarch in a society plagued with incurable patriarchy. My favourite story of Mataji comes from the evening of those Tibri Kachori’s. My father asked her out on a date and told her that he wanted to take her out, his only condition being- She wore a shirt and a pair of trousers. Mataji, my 93-year-old great-grandmother, a woman who had never worn anything but a Sari, and the occasional salwaar-kameez, took a moment’s hesitation and changed into my mother’s clothes and although they didn’t go out, my dad played her his favourite mix on his ratty stereo and they danced to the tunes of Stevie Wonder.

It’s later in the night, and I have accepted that these Kachori balls will not come to life today. I wrap the dough, put the mixture in dated Tupperware and call it a night.

In stating that my Grammy was perfect, I label myself a liar. She was fierce but temperamental. She was tough on the women that married into her family. There were things from traditions past that continued to live in her presence. My mother recollects a particularly sassy moment Mataji asked her to wrap the stew my grandmother had made for dinner in a polythene bag, spin it over her head and throw it as far as she could….

They say she eventually mellowed down, but that’s the thing with memories. Isn’t it? Names are forgotten, and moments documented in photographs are conflated with other ones. I can’t remember where I read this, but a wise woman said “Memory is always an approximation and through approximation, it becomes a generative practice. It mutates over time, over place, and over generations. This does not make it any less powerful or healing.” The chemical matter released, moving from neuron to neuron, within the synapse is differently composed every single time. So, the memory retrieved comes back a little skewed, a little altered. I’d like to believe that with each alteration, the dissension is lost, but happy memories with sprinklings of quirks are gained and they remain. Mataji, of a tiny stature, had a big personality that left a lasting impact on everyone she met.

It's a new morning, and the time it takes to restore a memory with little form or structure, is the time it has taken me to realise- I am incapable of making dishes with long waiting periods and staggering nostalgia. Thankfully instead of a ‘good morning' message from India this fine morning, there sits an image of a Dal Kachori made at home, with aloo ki Sabzi (the side dish I had conveniently forgotten) titled (and I imagine this in her husky, cheeky, giggly voice)–

“paade so punya kare, aur sunghe so dharmatma”

All in the span of a Day.

Saumya (she/her) is a freelance editor and writer currently working on commissioning and developing manuscripts for YA fiction and children’s non-fiction. When handed a plate full spicy potatoes x asafoetida–two things so beautifully Desi, she (almost) forgets to sporadically rant about all things third-culture, framing and reframing her breathless monologues into theatrical/ comedic narratives.

contact: saumyashawarma@gmail.com

Slurrrrp..

My mouth is watering already as I am reminded of the toothsome desi savoury.A routine occurrence turned into an eminent lucid saga!Way to go,your pen.Keep writing.